How LA deals with its homeless continues to evolve, and recognition of their property rights has compelled the city to modify its approach to cleaning and clearing the Skid Row sidewalks, a place many people reside and keep their belongings.

"You get tired of carrying it around," said Ken Owens, 64, who finds himself homeless waiting for his pension to kick in after his next birthday.

Last year, homeless advocates received a federal court order enforcing property rights, forbidding city cleanup crews from simply throwing away unattended items such as clothing or toiletries or ID.

For want of a workaround, Skid Row cleanup ground to a halt, homeless from elsewhere moved in and the area paid the price.

"It's sad the city saying because we can't take your property we ain't going to clean up anything," said Deborah Burton, once homeless, and now working as an organizer for the Los Angeles Community Action Network.

But it's not just the homeless and their advocates who felt that way.

"You had block after block that looked like shantytowns," said Estela Lopez, executive director of the Central City East Association.

Local

Get Los Angeles's latest local news on crime, entertainment, weather, schools, COVID, cost of living and more. Here's your go-to source for today's LA news.

Dealing with issues related to the homeless was a prime motivation for the Association to create two business improvement districts. For a decade, the one that encompasses Skid Row, the LA

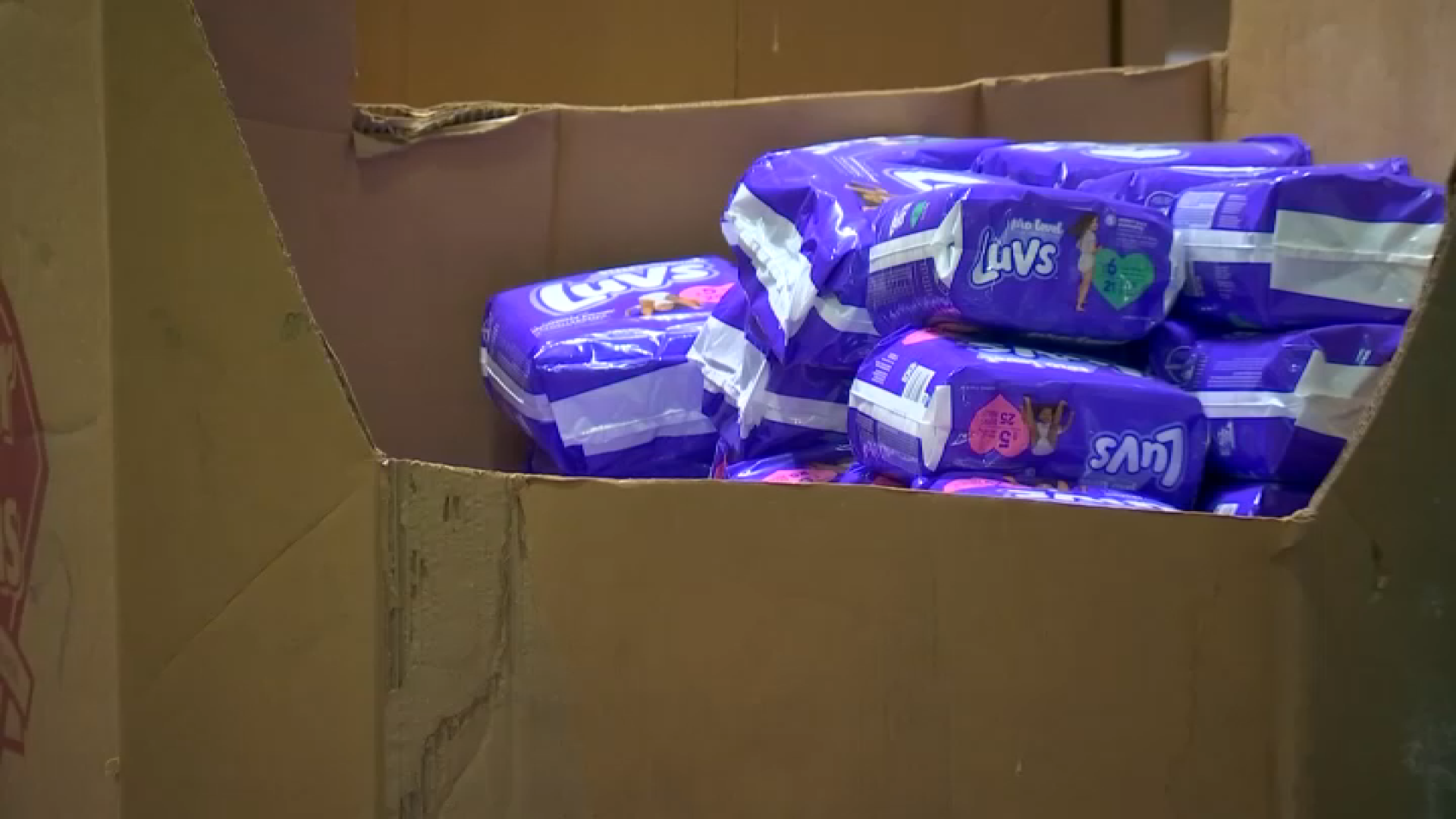

Downtown Industrial District, has funded a 7th Street check-in center that provides free storage for the homeless.

"For me, it's a nice place," Manuel Diaz said as he removed some shirts stored in his bin.

The program costs $100,000, not counting the value of the property that a District member provides at no charge, Lopez said. Members find it worthwhile, and not solely for altruistic reasons.

"All the possessions that are in this warehouse are not out on the street, blocking entrance to doorways, driveways and loading docks in this very busy industrial district."

Of course not everybody goes for it, and the district's red-shirted, bicycle-riding staffers will remove unattended items blocking passageways, and then, by policy, store them for pickup in a corner of the check-in center.

"Ninety-eight percent of people know if their stuff's not there, to come here," said George Peterman, director of operations.

For years, few followed the example of the Central City East Association.

But during the past year, pending the appeal of the federal injunction, the city of Los Angeles faced growing pressure to do something about the worsening situation in the Skid Row neighborhood southeast of downtown.

City Attorney Carmen Trutanich contacted the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health to look into the problem. It found an emerging health threat it termed a "crisis" and directed the city to take action.

In order to resume sidewalk cleaning and still comply with the injunction, city officials concluded they needed to set up a storage area for items removed from the sidewalk.

The city found space inside a property it had acquired years ago, once an Office Depot at the southeast corner of Temple and Alameda streets. A portion of it was transformed into a storeroom, and the city contracted with nonprofit organization Chrysalis to operate it.

It was there that items gleaned during June's Operation Healthy Streets cleanup were taken.

A visit to the site on Friday revealed most of the space is empty. There are fewer than a dozen and a half bags, containing mostly clothing, along with two shopping carts, and other miscellaneous items stored at the facility. To help with identification, each bag is tagged with the address of where the belongings were gathered.

City officials could not say how many other collections had been reclaimed by their owners.

Homeless advocates contend the city dragged its feet, but ultimately did the right thing.

"For the most part, Operation Healthy Streets did what the community has been asking for: cleaner streets, and respect our property rights," said Becky Dennison, co-director of LA CAN.

As it was, in Lavan et al v. City of Los Angeles, a panel of the federal Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals rejected the city's challenge and upheld the injunction.

The City Attorney's office said, at this point, the ruling does not change things, with the city already having developed the "workaround" policy for complying with the injunction, and the city once again has a calendar of regularly scheduled cleanings.

Besides setting up the Temple Street storeroom last spring, the city also donated 500 additional storage bins to the 7th Street check in, boosting its total to 1,164. They have quickly been put to use, Lopez said.

Out on the street, Dennison believes more of the homeless, with advance cleaning notice, are gathering up their belongings in preparation for the crews coming, and leaving less of their belongings behind. For that reason, she doubts the city facility on Temple will ever see much property.

Still, she anticipates another looming legal confrontation over the city ordinance that prohibits leaving items on the sidewalk. If the City Attorney's office prosecutes under this ordinance, Dennison expects its constitutionality will be challenged.