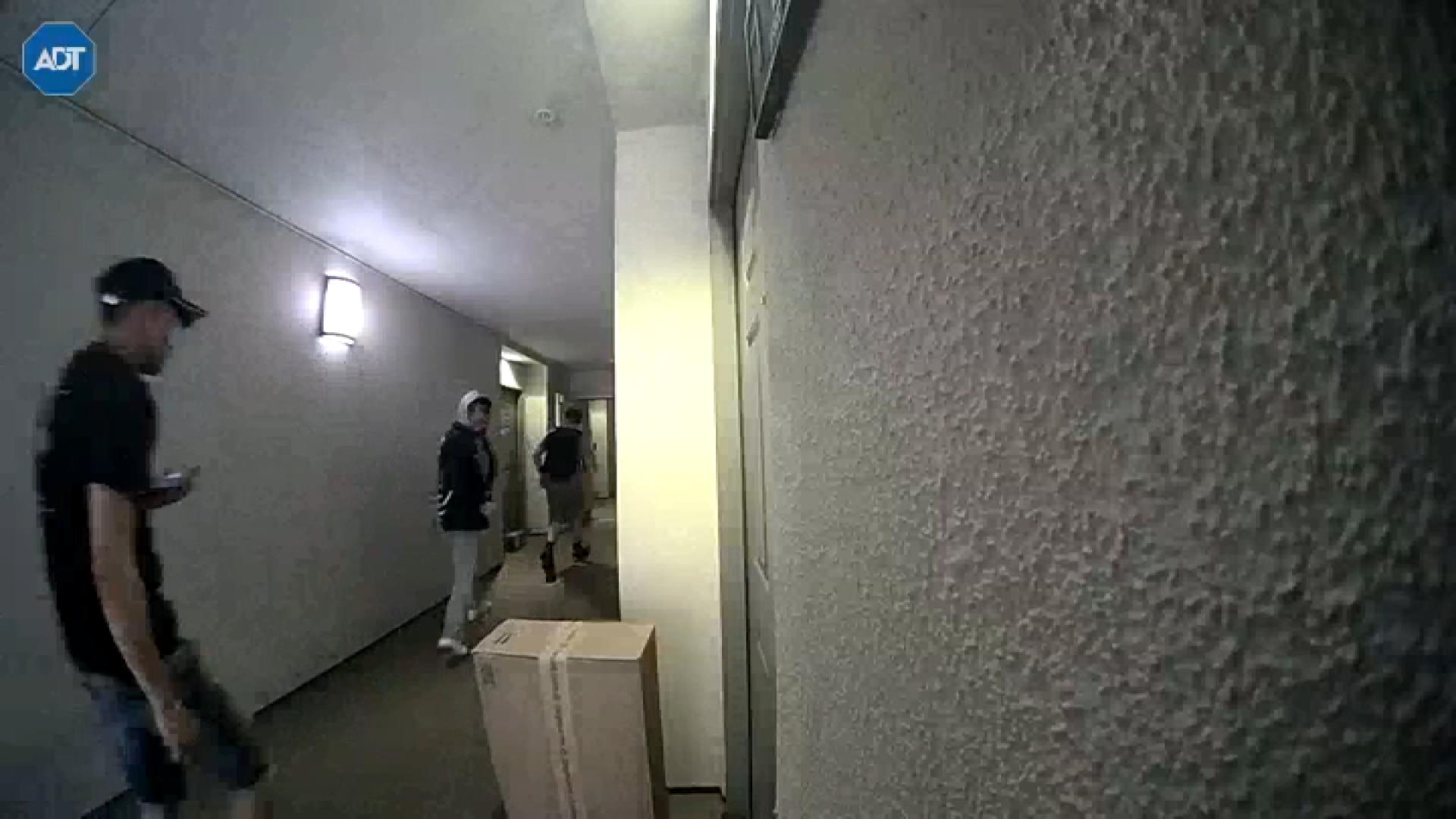

At 4:35 a.m. in Hollywood, even the clubbers and streetwalkers have already called it a night. Few early-risers have begun the new day.

But suddenly, on a quiet residential stretch of Las Palmas Avenue, a row of LAPD patrol cars pulls up. Officers burst out of the doors and walk briskly to one of those classic court-style apartment buildings.

One officer niftily picks the lock on the front gate, and most of his colleagues head to the hallway outside the designated unit on the second floor. Others take strategic positions -- just in case.

A series of forceful knocks on the door breaks the early morning silence, and then comes an authoritative voice.

"LAPD. Open the door!"

It's only the first stop of half-dozen this particular morning for the Los Angeles Police Department's trail-blazing Parole/Probation Impact Team, focusing on felons released from prison and now living in the community.

"We started this because we noticed parolees were causing a lot of the crime in our division," said Detective JIm Hays, the long-time homicide investigator who launched the unit in the Hollywood station.

Then, 2011 brought Assembly Bill 109, the change in state law that enacted so-called realignment.

Local

Get Los Angeles's latest local news on crime, entertainment, weather, schools, COVID, cost of living and more. Here's your go-to source for today's LA news.

One impact is that as thousands of felons finish their prison terms, a significant percentage are released not to the supervision of state parole, but instead come under so-called community supervision by county probation and local law enforcement.

Working in conjunction with the Los Angeles County Probation Department, Hollywood's Impact Team took on the added responsibility of monitoring the AB 109 community releases.

In much of California, those AB 109 early releases have been blamed for increases in property crime rates this past year. But In Los Angeles, property crime rates have remained flat, according to LAPD statistics.

Chief Charlie Beck gives much of the credit to the monitoring teams that have now been established in all of department's station areas city-wide, a commitment of some 150 officers.

At Hollywood station, the number of community release offenders fluctuates between 30 and 80, Hays said. Citywide, the number at any one time can approach 1,000, the figure varying as

some finish their supervision and new releases arrive from prison.

When offenders on community supervision are found in violation of the terms of their release, they can face new charges, or be held up to 10 days on so-called "flash" incarceration, said Sgt. Chad

Costello, who runs the parole side of the Hollywood impact team.

It is possible to revoke community release and send the offender to county jail for more than ten days, but this is rarely done.

During the Hollywood impact teams's Tuesday morning mission, three released felons were discovered not living where they said they were. If they don't notify their probation officers of their new addresses, arrest warrants will likely be issued, Costello said.

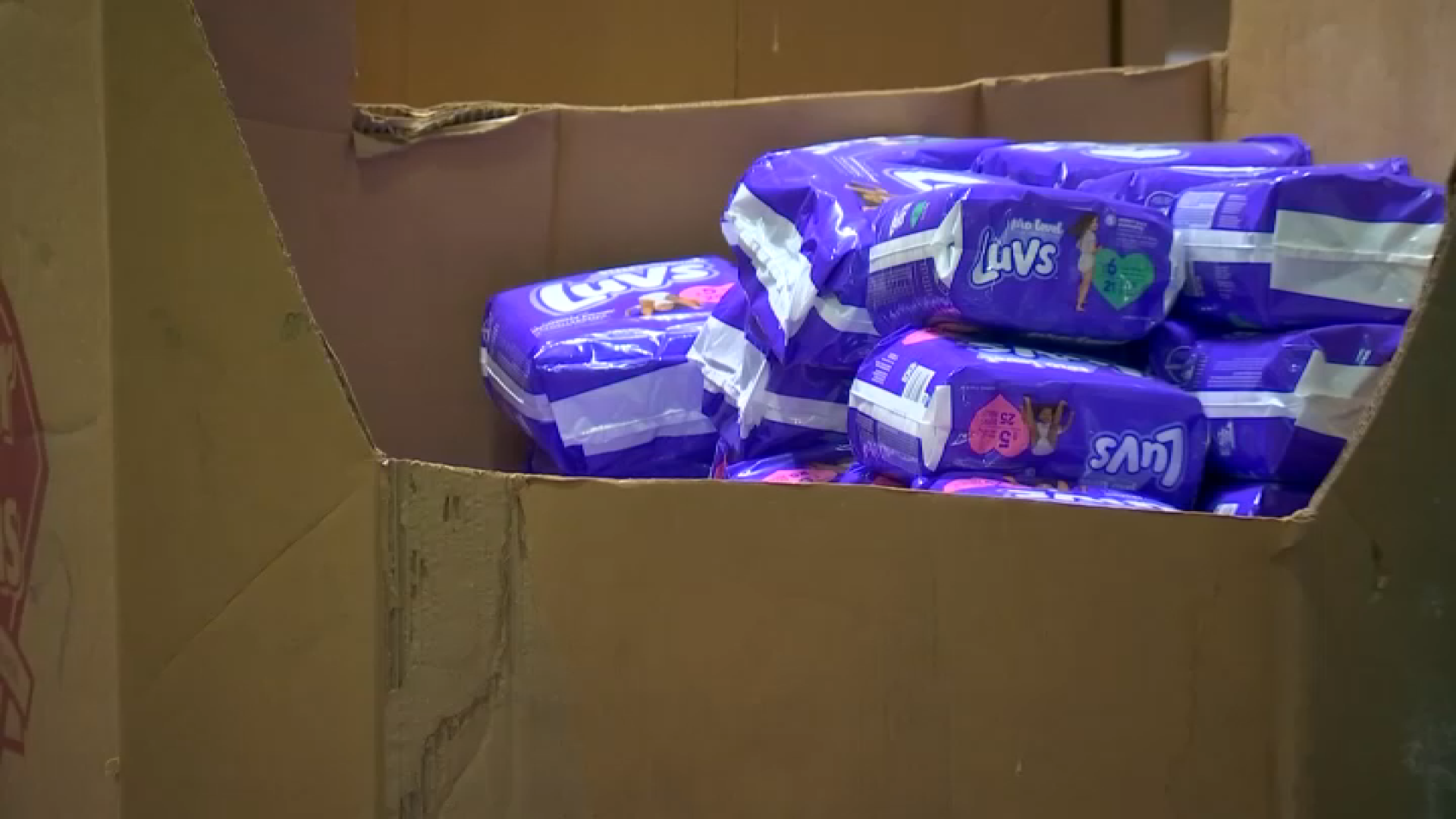

At two other locations, the homes of narcotics offenders, searches found drugs, and the men were taken back into custody.

"They're not solving the problem," said Christopher Doop as he squatted outside in handcuffs, waiting to be transported.

For Doop, this was the third time the LAPD Impact team had come to his residence, and the third time he had been taken back into custody for alleged violations.

After the expected flash incarceration, Doop likely will be back on the street in 10 days.

Like Doop, offenders on supervised release are subject to search without a warrant or even probable cause.

The fugitive suspect in the Northridge home invasion kidnapping, Tobias Summers, was on community release at the time. In fact, he had been arrested in January.

But after flash incarceration, he was back on the street nine days later.

Flash incarceration can be effective in getting the offender's attention, said Margarita Perez, the assistant probation chief who previously served as deputy director of the state's Division of Adult Parole Operations.

But at street level, officers express frustration that many re-arrested offenders are returned to the community so quickly.

"It seems to us, anyway, that it's not very successful at keeping them in custody," Costello said. "So all we do is continue to do our checks on them. And if they're in violation, put them back in jail."

Los Angeles may now be at or near the peak of community releases, Hayes believes.

Only so-called "non, non, nons" (prison inmates with convictions for crimes deemed non-serious, non-violent, non-sexual) may be released to the community. Those pre-2011 sentences are being served out, and in a few more years, few in that category will remain in prison.

Since realignment took effect, the "non, non, nons" have been sentenced to terms in county jail, not prison. Some are given so called "split terms," which include a period of supervision after

release.

The judges in some counties hand down a significant percentage of split sentences.

But in LA County, only 5 percent are split, according to Hayes. The remaining 95 percentage do not have to check in with probation, and are not subject to searches without a warrant.