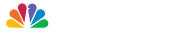

- Air pollution, which is primarily the result of burning fossil fuels, takes 2.2 years of the global life expectancy for each person, according to a new report out Tuesday from the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago (EPIC).

- For comparison, that's a smidge more the decline in average life expectancy caused by smoking, more than three times that of alcohol use and unsafe water, six times that of HIV/AIDS, and 89 times that of conflict and terrorism.

Air pollution, which is primarily the result of burning fossil fuels, takes 2.2 years off the average global life expectancy, according to a new report out Tuesday from the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago (EPIC).

The Air Quality Life Index, or AQLI, finds that taken together, air pollution takes a collective 17 billion years of life, and reducing air pollution to meet international health guidelines would increase the global average life expectancy from roughly 72 to 74.2 years

Get Southern California news, weather forecasts and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC LA newsletters.

Firsthand cigarette smoke reduces life expectancy by 1.9 years, on average, according to the report. Alcohol and drug use reduce life expectancy by nine months on average, unsafe water and sanitation reduce expectancy by seven months, HIV and AIDS reduce life expectancy by four months, malaria reduces average life by three months, and conflict and terrorism reduce life expectancy by seven days, the report said.

The AQLI report is notable because its estimate of the impact on particulate pollution on human life expectancy is based on research that allows it to show causation, not just correlation. "Because of the way these studies were designed - and the quite fortuitous set of policies that enabled that design, they established a causal, rather than a correlative, relationship between particulate matter exposure and mortality," Christa Hasenkopf, the director of AQLI, told CNBC.

Air pollution is so dangerous because it is impossible to avoid, especially for people who live in particularly polluted locations, the report says. "Whereas it is possible to quit smoking or take precautions against diseases, everyone must breathe air. Thus, air pollution affects many more people than any of these other conditions," the report says.

Money Report

Sixty percent of particulate matter air pollution is caused by fossil fuel combustion, 18% comes from natural sources (including dust, sea salt, and wildfires), and 22% comes from other human activities.

The report, developed by the University of Chicago's Michael Greenstone and his team at the EPIC, is a measurement of the air pollution in 2020, when the Covid-19 pandemic was reducing activity and transportation.

The massive contraction of activity reduced global pollution levels only by a tiny bit. Population weighted-average particulate matter declined from 27.7 micrograms (one-millionth of a gram) per cubic meter of air to 27.5 micrograms per cubic meter of air between 2019 and 2020, according to the report.

And in South Asia, where air pollution is the most dire, the air pollution rose in 2020 from the year prior. India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal are among the most polluted countries in the world.

Particulate matter air pollution is suspended in the air and categorized by its size. The smaller it is, the deeper it can get into the body. Particulate matter with a diameter of less than 10 micrometers, often designated PM10, can pass through the hairs in the nose, down the respiratory tract and into the lungs.

Smaller particulate matter with a diameter less than 2.5 micrometers, often designated as PM2.5, is about 3% the diameter of a human hair and can get into the bloodstream by way of the lungs' alveoli. It can affect blood flow, eventually causing a stroke, heart attack and other health issues.

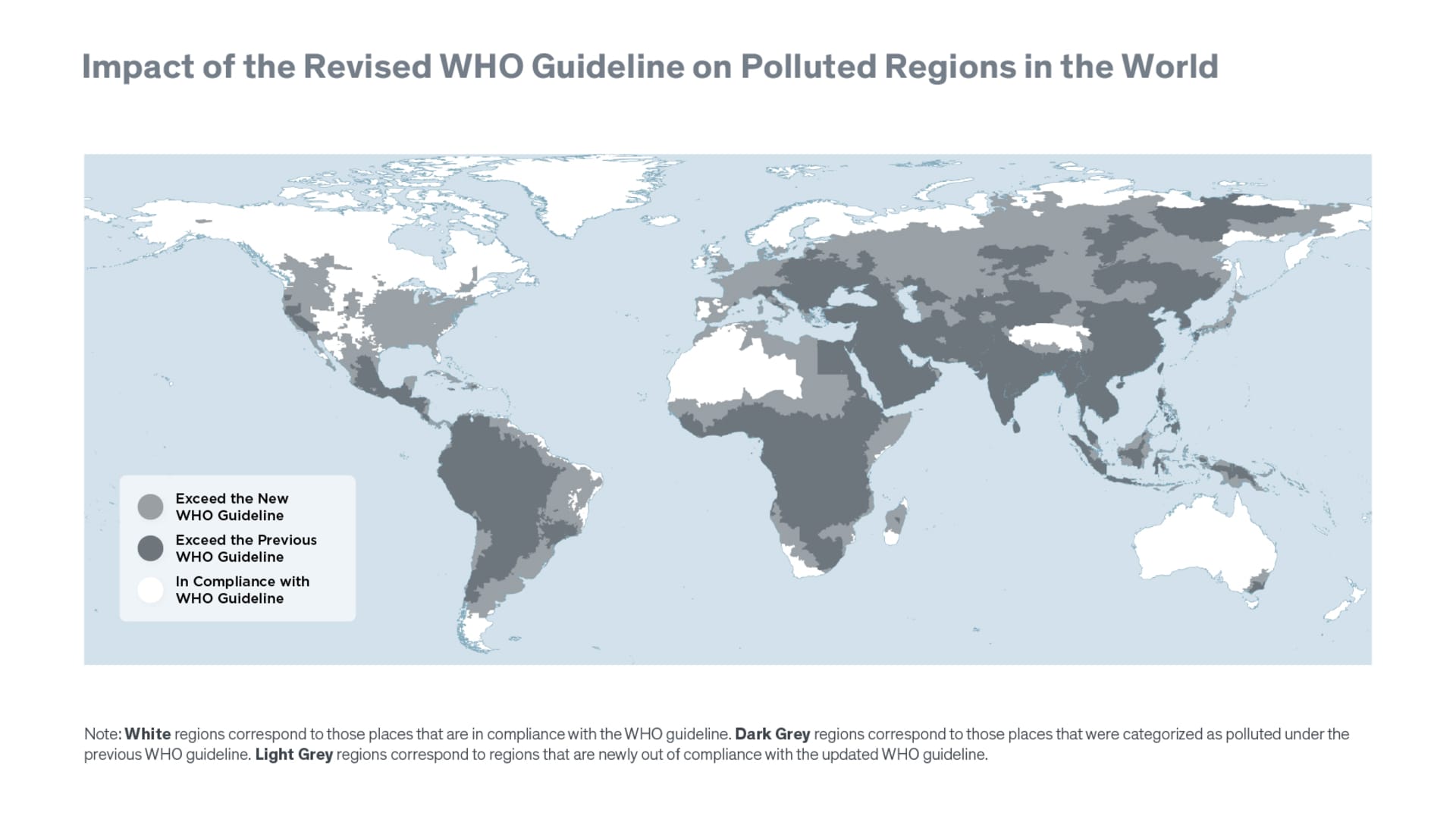

When the World Health Organization first published air quality guidance in 2005, it said the acceptable levels of air pollution was less than 10 micrograms per cubic meter. In September, the World Health Organization changed its benchmark guidelines to below 5 micrograms per cubic meter.

Currently, 97.3% of the global population, equaling 7.4 billion people, live in places where the air quality does not pass the recommended 5 micrograms per cubic meter limit recommended by the WHO for particulate matter with a diameter of less than 2.5 micrometers.

"This report reaffirms that particulate pollution is the greatest global health threat," wrote Greenstone, who was previously the chief economist for former President Barack Obama's Council of Economic Advisers. "Yet we also see the opportunity for progress. Air pollution is a winnable challenge. It just requires effective policies."

For example, China has been able to dramatically improve its air quality. In 2014, after a year in which China had record levels of pollution, the then premier, Li Keqiang, declared a "war against pollution." The government spent money to combat pollution and was able to reduce particulate pollution by 39.6%, the report says.

Despite China's progress, the air pollution levels in China are still more than what the WHO recommends.

"It is important to note that air pollution is also deeply intertwined with climate change. Both challenges are primarily caused by the same culprit: fossil fuel emissions from power plants, vehicles, and other industrial sources," the report's executive summary says. "These challenges also present a rare win-win opportunity, because policy can simultaneously reduce dependence on fossil fuels that will allow people to live longer and healthier lives and reduce the costs of climate change."

The American Medical Association, the country's largest physician trade group, voted on Monday to adopt a policy to declare climate change a public health crisis.

"The scientific evidence is clear — our patients are already facing adverse health effects associated with climate change, from heat-related injuries, vector-borne diseases and air pollution from wildfires, to worsening seasonal allergies and storm-related illness and injuries. Like the COVID-19 pandemic, the climate crisis will disproportionately impact the health of historically marginalized communities," said AMA Board Member Ilse R. Levin, in a written statement announcing the vote. "Taking action now won't reverse all of the harm done, but it will help prevent further damage to our planet and our patients' health and well-being.