A federal judge has reduced the damage award, but upheld a jury's finding that police use of a Taser killed a North Carolina teenager.

"This is a dangerous device," said John Burton, the Pasadena-based lead attorney for the family of Darryl Turner.

Burton said two of the findings upheld are key.

"That Tasers, when they're shot into the chest, can cause cardiac sudden death,” Burton said. “And that Taser failed to warn its users about that."

That federal court decision could challenge the law enforcement niche that the electrical Taser control device was designed to fill. Manufacturer Taser International, Inc. is fighting back and pledges an appeal.

The Taser was developed over decades in response to a groundswell of demand for devices enabling officers to control combative suspects without grappling, clubbing, or having to resort to deadly force.

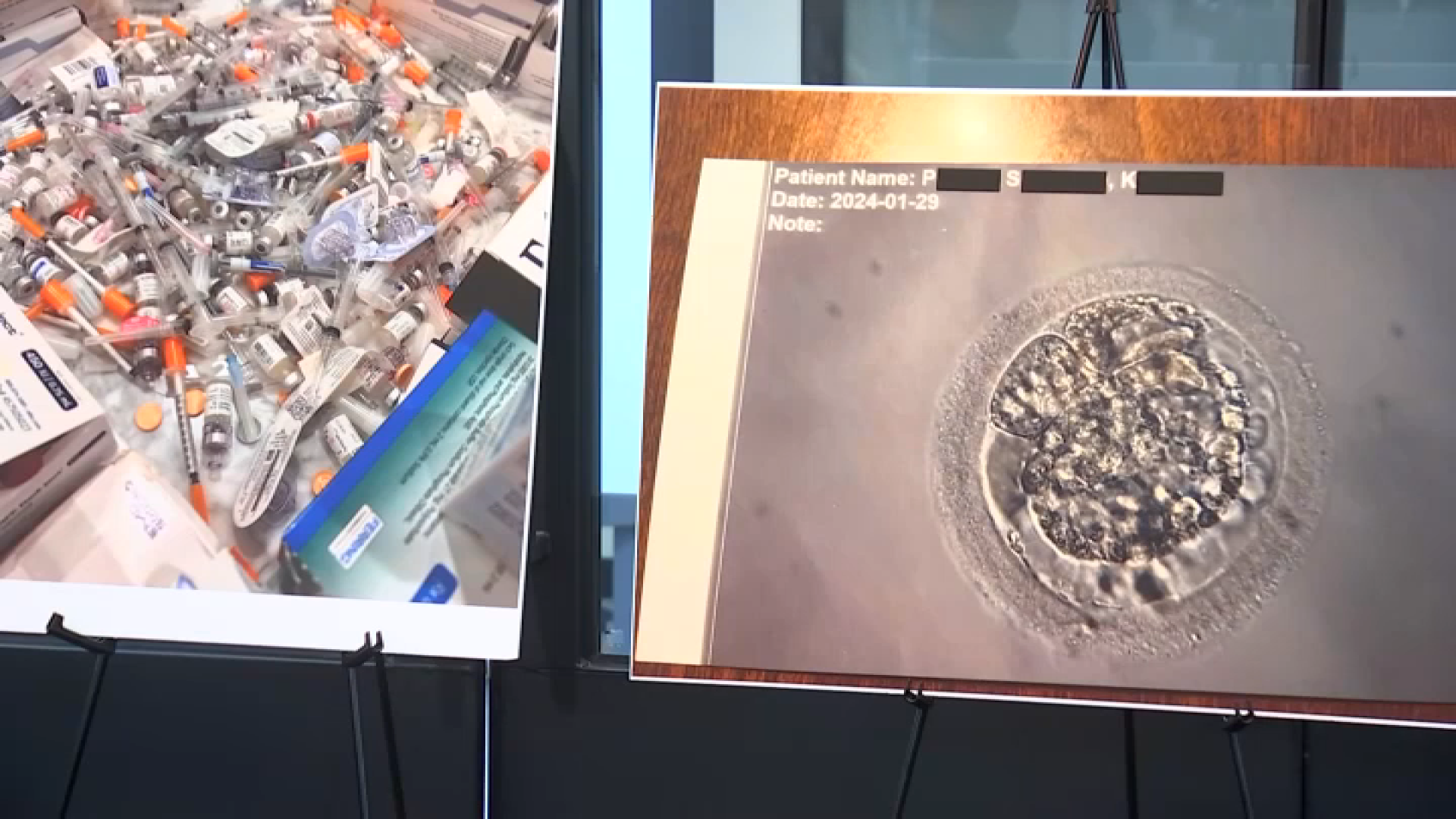

It works by sending electrical current through the body, either by direct application, or by firing two electrode darts attached to the power source by wires.

Local

Get Los Angeles's latest local news on crime, entertainment, weather, schools, COVID, cost of living and more. Here's your go-to source for today's LA news.

The Taser, a registered trademark name, is deemed a non-lethal weapon. But the Federal District Court for Western North Carolina has now made the finding that, in the 2008 Turner incident, that use of a Taser can stop the heart.

Police were called to a Charlotte market after employee Turner, 17, was terminated and--as witnesses testified and a security video showed--began acting out. The responding officer fired his Taser, which initially did not stop Turner.

Evidence at trial showed the Taser trigger was held down 37 seconds before Turner dropped. Officer Jerry Dawson administered Turner a second shock of five seconds. The teen was non-responsive and paramedics could not revive him.

The darts had struck Turner in the chest. The medical expert called by his family, Douglas Zipes, MD, testified his conclusion that the Taser's electrical current disrupted Turner's heart rhythm and ultimately caused his heart to stop.

Taser's attorneys contended that Turner had an existing heart condition making him susceptible to cardiac arrest.

Last summer, the jury found in the family's favor, and set damages at $10 million. Taser filed a motion challenging the verdict.

Tuesday, Chief District Judge Robert J. Conrad Jr. upheld the jury's "factual finding," but reduced the damages by $5 million. Conrad then further deducted the $650,000 settlement from the City of Charlotte, and $40,000 from Workers' Comp, bringing the final judgment to $4,372,399.

"The jury decided that Taser's product, used as directed, caused Turner's death. This court will not displace that factual finding," Conrad wrote in his a 34-page ruling.

Turner's family could request a new trial to seek higher damages, but is not expected to do so.

Assuming the judgment is entered, Taser International "intends to appeal based on exclusion of key evidence and other errors," according to a statement issued by the company Wednesday.

Taser contends the officer misused the device, and that the judge erred by excluding jury instructions related to that, and to "Mr. Turner's contributory negligence."

The allegation that tasing can cause ventricular fibrillation has been raised in a number of cases in the past decade, but rarely have they gone to verdict, and rarely have those verdicts gone against Taser.

The company's first significant jury setback came in 2008, when a California jury found that Taser was 15 percent responsible for the 2005 death of a suspect in Salinas.

Robert Heston's "methamphetamine intoxication" was cited as a more significant factor in that case. As with the Turner case, the judge later reduced the damage award, but upheld the jury's factual finding.

Following the Heston case, Taser "issued revised warnings that included language about the risks of extended, prolonged, or multiple Taser ... applications on exhausted or otherwise compromised subjects," according to a 2008 Taser Training and Legal Bulletin.

It's believed the Turner case is the first in which Taser has been found to be the primary cause of death.

In its statement, Taser International defended the safety of its product, citing a study released last year by the U.S. Department of Justice that "current research does not support a substantially increased risk of cardiac arrhythmnia in field situations, even if the [Taser] darts strike the front of the chest."

There was testimony in the Turner trial that Taser training materials taught officers to aim for the target's "center of mass" and "depicted chest shots as examples," according to Judge Conrad's written ruling.

After Turner's death and the Heston verdict, Taser issued new targeting guidelines. The training video on TASER International's website states that in Oct. 2009, Taser "lowered the preferred target area by about five inches for shots to the front of the body."

The video refers to the controversy over possible effects to the heart, but notes the main reasons for the target adjustment are for consistency with other Taser products, and for increased effectiveness when the darts land lower, in areas where there is more muscle mass.

"The preferred target zones have less to do with safety, and more to do with effective risk managment for law enforcement agencies," said Rick Guilbault, identified on the video as VP Training & Education.

Some law enforcement agencies that equip officers with Tasers have also revised targeting guidelines. In Feb. 2011, in "Use of Force Directive 4.2," the Los Angeles Police Department listed the "back, navel, or belt line" as "optimum target areas...for probes."

Burton conceded there are situations where tasing would be law enforcement's "best option."

But he's not convinced the new targeting guideline cures the heart safety concern.

"I think it still understates the danger," Burton said, adding that he thinks it could be "difficult for officers to follow" in some circumstances

Follow NBCLA for the latest LA news, events and entertainment: iPhone/iPad App | Facebook | Twitter | Google+ | Instagram | RSS | Text Alerts | Email Alerts