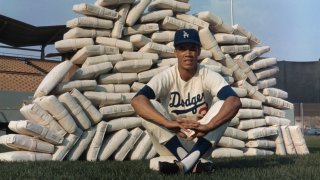

Dodgers great and seven-time All-Star Maury Wills has died at age 89, the team announced Tuesday.

The prolific base-stealing shortstop was an integral part of three World Series championship teams.

"The Los Angeles Dodgers are saddened by the passing of Dodger legend Maury Wills," the Dodgers said in a tweet. "Our thoughts are with Wills’ family, teammates and friends."

Wills died Monday night at his home in Arizona, the team said. No cause of death was provided.

Get Southern California news, weather forecasts and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC LA newsletters.

Wills was a key player on World Series winning teams in 1959, 1963 and 1965 in a run of eight seasons with the Dodgers. He played for Pittsburgh and Montreal before a return to the Dodgers in 1969.

The team will wear a patch in his memory for the rest of the season.

Local

Get Los Angeles's latest local news on crime, entertainment, weather, schools, COVID, cost of living and more. Here's your go-to source for today's LA news.

“Maury Wills was one of the most exciting Dodgers of all time,” team president and CEO Stan Kasten said. “He changed baseball with his base-running and made the stolen base an important part of the game. He was very instrumental in the success of the Dodgers with three world championships.”

He retired after the 1972 season as one of the all-time greats in stolen bases. He led the National League in stolen bases from 1960-1965, representing a constant threat on the base paths for opposing pitchers and catchers.

Wills batted .281 with 2,134 hits and 586 stolen bases in 1,942 games during an illustrious 14-year career. He earned the National League MVP in 1962. The seven-time All-Star won Gold Glove Awards in 1961 and 1962, the same year the All-Star game was played in his hometown of Washington, D.C.

Wills stayed at home with his family instead of at the team hotel for the All-Star Game. He arrived at the ballpark carrying a Dodgers bag and wearing a Dodgers shirt, but the security guard wouldn’t let him in, saying he was too small to be a ballplayer.

Wills suggested the guard escort him to the NL clubhouse door, where he would wait while the guard asked the players to confirm his identity.

"So we walk down there and baseball players have a sick sense of humor, because when I stood in front of the door, with my Dodger shirt and duffel bag, and the man opened the door and said, 'Anybody in here know this boy?' and they all looked at me and said, 'Never saw him before,” Wills told The Washington Post in 2015.

After the game, Wills left with his MVP trophy and showed it to the guard.

"He still didn’t believe me, he thought maybe I was carrying it for somebody,” Wills told the Post.

Wills was fast, but his strategic approach to base stealing raised the bar for base running. He studied pitchers' motions to the plate, developing a keen eye for pickoff moves and a base stealing opportunity.

Wills managed the Seattle Mariners from 1980-81. He was 26-56 with a winning percentage of .317.

Wills’ tenure managing the Mariners was largely regarded as a disaster and he was criticized for his lack of managerial experience. It was evident in the numerous gaffes he committed, including calling for a relief pitcher when nobody was warming up in the bullpen and holding up a game for several minutes while looking for a pinch hitter.

On April 25, 1981, he ordered the Mariners’ ground crew to extend the batter’s box a foot longer toward the mound than regulation allowed. Oakland manager Billy Martin noticed and asked home plate umpire Bill Kunkel to investigate.

Kunkel questioned the head groundskeeper, who admitted Wills had ordered the change. Wills said it was to help his players stay in the box. However, Martin suspected it was to give the Mariners an advantage against Oakland’s breaking-ball pitchers. Wills was suspended for two games by the American League and fined $500.

Years later, Wills admitted he probably should have gotten more experience as a minor league manager before being hired in the big leagues.

Wills struggled with addictions to alcohol and cocaine until getting sober in 1989. He credited Dodgers pitching great Don Newcombe, who overcame his own alcohol problems, with helping him. Newcombe died in 2109.

"I’m standing here with the man who saved my life,” Wills said of Newcombe. “He was a channel for God’s love for me because he chased me all over Los Angeles trying to help me and I just couldn’t understand that. But he persevered, he wouldn’t give in and my life is wonderful today because of Don Newcombe.”

Born Maurice Morning Wills in Washington, D.C., on Oct. 2, 1932, he was a three-sport standout at Cardozo Senior High. He earned All-City honors as a quarterback in football, in basketball and as a pitcher in baseball when he was nicknamed Sonny.

In 1948, he played on the school’s undefeated football team, which never gave up any points. On the mound, Wills threw a one-hitter and struck out 17 in a game in 1950. The school’s baseball field is named in his honor.

Wills has his own museum in Fargo, North Dakota, where he was a coach and instructor for the Fargo-Moorhead RedHawks from 1996-97.

He is survived by wife Carla, and children Barry, Micki, Bump, Anita, Susan Quam and Wendi Jo Wills. Bump was a former major league second baseman who played for Texas and the Chicago Cubs.