- Siraba Keita, a Bronx resident from Mali, lived in an apartment building that was the site of a deadly fire in January. Her bank froze her savings shortly after, due to a court order that resulted from old credit card debt.

- Many states, including New York, have laws that are supposed to leave a certain portion of a bank account unfrozen.

- Delays in accessing funds can have serious knock-on effects for vulnerable Americans.

Siraba Keita survived New York's deadliest fire in decades — only to see her bank freeze the savings she needed to pick up the pieces.

Her story reflects the hardship of many low-income Americans in a system that seems to prioritize debt collectors over a bank's customers, according to consumer advocates.

Keita and her four children lived in an apartment building on East 181st Street in the Bronx, where a blaze killed 17 people on Jan. 9. The family was on the third floor of the 19-story complex — the same floor where a faulty space heater ignited the flames.

"We lost everything, not just the house — clothes, shoes, everything," said Keita, 39, an immigrant from Mali, in West Africa.

When Keita, a J.P. Morgan Chase customer, tried using her bank card shortly thereafter, the transaction was denied. Unbeknownst to Keita, a creditor had gotten a court order to freeze her money — the vestiges of old credit card debt that had spiraled out of control.

Money Report

New York law automatically protects up to $3,600 from such a freeze; additional funds like monthly child tax credit payments may also be protected. Many states have variations of these rules to help customers subsist while settling a debt dispute, and federal law offers immunity to benefits like Social Security.

But Chase withheld all of Keita's savings — more than $5,000 — for weeks, despite several trips to her local bank branch and repeated phone calls, she and her attorney said.

Prior to the fire, Keita had been living on her savings, government benefits like food stamps and by selling her jewelry. She'd stopped working as a nursing assistant to care for her 3-year-old son, who has autism.

"I have all my money in there," Keita said of her account. "This was all my life."

CNBC reached out for comment from the bank, but a Chase spokesman said they were unable to discuss specifics of Keita's case due to privacy reasons.

"When we receive a restraining notice tied to a New York court-ordered judgment against a customer to freeze funds they owe to a creditor, we comply with the law and notify our customers in writing to explain what is happening and the steps they need to take to gain access to exempted funds," the spokesman said.

'Dickensian times'

CNBC identified other individuals who, like Keita, believe their bank broke the law by freezing funds improperly due to a debt judgment.

Low earners bear the brunt of this — a group most likely to turn to high-interest debt but with the least ability to repay it, according to consumer advocates.

While it's unclear exactly how many people this happens to each year, debt collectors have been suing consumers more frequently in court.

The number of debt-collection lawsuits in state civil court more than doubled nationwide, to about 4 million, from 1993 to 2013, according to The Pew Charitable Trusts, a nonpartisan research organization. Available data suggests that trend has continued, it said.

Such lawsuits make up about one of every four civil cases in state court; the ratio was one in nine in the early 90s, Pew found.

Debt lawsuits are likely to spike as most pandemic-era financial protections (like eviction and foreclosure moratoria) come to an end, according to the National Consumer Law Center.

Debt collection was already the second-largest source of complaints to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in 2020. Over half were for attempts to collect on a debt that wasn't owed.

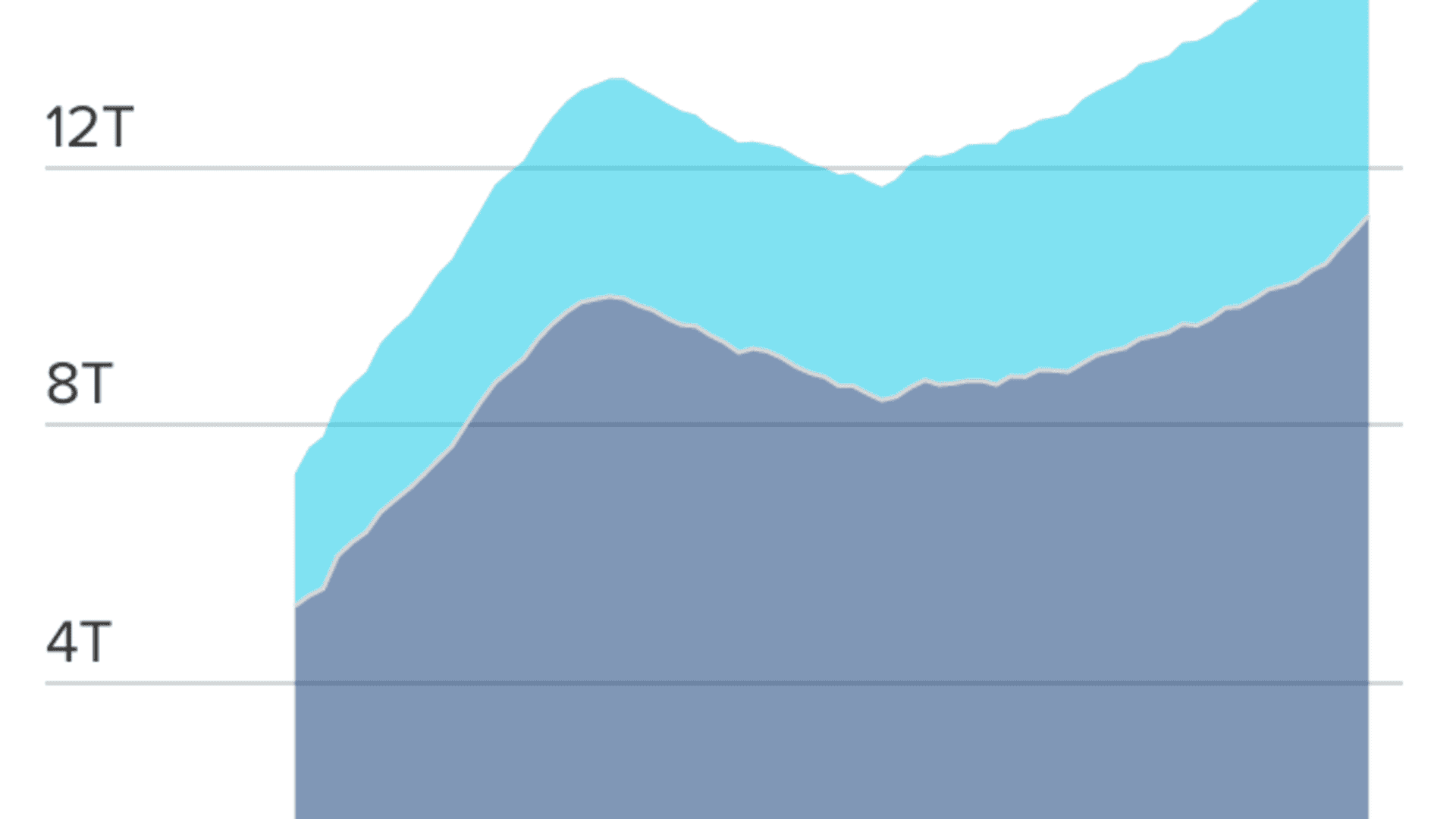

And household debt, at an all-time high of $16 trillion, grew at its fastest pace since 2007 in the fourth quarter, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

"I've been seeing it more than I would like to," Mary McCune, an attorney at Legal Services NYC, who is representing Keita, said of banks freezing funds they likely shouldn't.

"It feels like we're in Dickensian times sometimes," McCune added. "It's the criminalization of poverty."

Other consumer advocates think banks have gotten better at complying with the law, though.

"In years past, I've certainly seen banks do that," according to Cliff Dorsen, an attorney at Skaar and Feagle in Georgia, which handles consumer rights cases. "I haven't seen it in a while."

"It doesn't mean they're not doing it," he added. "But no one's calling us about it."

'Not a bad person'

In Keita's case, she owed Discover Bank about $5,200 in credit-card debt (including principal and interest), documents show. She tried paying off the debt, in installments of $100 to $200 a month, but couldn't keep up. Discouraged, she stopped looking at notices. She doesn't use credit cards anymore.

"I didn't mean for it to end up like that," Keita said. "I'm not a bad person. I can't pay."

Some customers were unaware the debt even existed, only learning of it after their bank turned off the spigot. Even then, they weren't privy to the debt's origination — leaving them guessing as to its authenticity and navigating a legal morass.

Taneesha Woodyear, 49, learned of a $2,400 debt only after Chase called to notify her of an overdrawn account.

She ultimately waited more than five months, from May to October 2021, to access her savings.

"I saved my money for a rainy day," said Woodyear, who lives in Harlem. "And then it's a rainy day and I can't get the umbrella."

The bank froze her funds after getting a restraining notice from Judgment Recovery Partners LLC, a debt collector based in New York. The judgment was over a decade old, dating from January 2011, according to documents filed in the Civil Court of the City of New York. (A different debt buyer, Advantage Assets II Inc., had obtained the 2011 judgment; Judgment Recovery Partners later bought the debt and was trying to collect.)

It was a "default" judgment, meaning the court automatically ruled in favor of the debt collector because Woodyear, who didn't know of the debt, didn't show up to a hearing. (About 70% of debt-collection cases are decided by such default judgments, according to Pew.) Interest keeps accruing on such loans, though — and Woodyear's debt had ballooned to more than $4,600.

Collectors are third parties that buy up loans (like medical and student debt) at a discount and try to recoup the funds.

A common experience

It's not uncommon for consumers not to know of a debt until it's too late, according to Carolyn Carter, deputy director of the National Consumer Law Center.

For example, she said: What if a renter moves out of an apartment, thinking it's in fine condition, but the landlord sues for cleaning costs? The renter may not think they owe money if they never receive that bill. Or, perhaps you co-sign a car loan for a friend, child or aunt, but they fall behind on payments years later. You may be on the hook and not suspect it.

The court wouldn't tell Woodyear or her attorneys where her debt initially came from; she suspects it was from around the time her mom died, when her finances temporarily fell into disarray.

Woodyear had $7,180 in her bank account — well exceeding the $4,600 debt judgment. However, New York state law lets banks freeze twice the total amount of the judgment (in this case, the restraint amounted to roughly $9,200), meaning her whole account was locked.

In so doing, her attorneys, Ahmad Keshavarz and Emma Caterine, claim the bank broke state law (the Exempt Income Protection Act) which should have left $3,600 untouched.

Pandemic-era rules should have also granted her access to other funds (like federal stimulus payments from March 2021 and, later, child tax credit payments for her 11-year-old), the attorneys said.

The freeze persisted even after a judge threw out Woodyear's debt judgment, on May 25, according to court documents. Chase ultimately granted access in the fall, months later.

"I had a struggle paying my rent, paying my bills, even buying my 11-year-old clothes, sneakers, toiletries," said Woodyear. "It's your money, and the bank is saying you can't have it."

A spokesman for Chase couldn't comment on the specifics of Woodyear's case for privacy reasons. He reiterated that the bank follows the law and notifies customers of steps to take to access their funds.

A range of rules

Every state but one (Delaware) allows creditors seize bank accounts to satisfy debt, according to Carter of the National Consumer Law Center.

Like New York, these states have exemption laws that protect certain funds from seizure. They vary greatly between states.

Arizona, for example, exempts just $300 in a bank account. But other assets are off-limits, too: a home worth up to $250,000, a car worth $6,000, and $6,000 in household goods, according to the National Consumer Law Center.

Mississippi protects a home worth $75,000; it gives an additional "wildcard" exemption for $10,000, which debtors can apply to any property (a car, bank account, household goods).

Six states (California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Nevada, New York and Washington) have "self-executing" rules, Carter said. They automatically exempt a certain dollar amount in bank accounts from garnishment, without action on a consumer's part, she said.

That means in most states, bank funds can be frozen as soon as a debt collector furnishes a garnishment order. Consumers must take procedural steps (typically, filing court papers or attending hearings) to claim the protections.

Even if they can navigate the legal thicket, these processes can take weeks, maybe months, according to consumer advocates. Delays can have cascading effects: Outstanding checks may bounce, late fees can pile up, landlords may move to evict, credit scores may suffer, and so on.

'Afraid to check'

New York has among the strongest protections relative to other states, according to the National Consumer Law Center.

Yet even there, customers still need to file paperwork to access some protected funds (like unemployment benefits) if they exceed the $3,600 blanket threshold. The forms must be filed to the bank and creditor within 20 days; then the creditor has a week to object in court. Assuming this process goes smoothly, the bank frees up the money.

Aboubacar, 58, an immigrant from Cote d'Ivoire, in West Africa, filed that Exemption Claim Form within the 20-day window, according to Susan Shin, legal director of the New Economy Project, which gives advice to low-income New York City residents, including Aboubacar. (He asked to use only his first name, for privacy reasons.)

Capital One, his bank, left about $10,000 unfrozen. But it also withheld thousands of dollars of protected funds, including a Small Business Administration disaster loan, unemployment benefits and child tax credit payments, according to bank records.

He waited from September 2021, to January 2022, for Capital One to free up the money. Aboubacar's debt judgment dated to 2000; its source is a mystery. Since the judgment was more than 20 years old, it wasn't legally enforceable since it exceeded New York's statute of limitation, Shin said.

A single father of four, Aboubacar drives for a ride-share service and made about $25,000 a year at the time his account was frozen.

"His income puts him and his family below the federal poverty line, and their financial hardship was greatly exacerbated by the months-long restraint," Shin said.

A Capital One spokesperson said the bank acted lawfully in Aboubacar's case.

The bank "never received a signed and dated exemption claim form from the customer," according to the bank spokesperson. That triggered a lengthy process involving a court hearing, and the relay of the court's decision to the NYC Marshal's office, the plaintiff's attorney's office, and then Capital One to process the order, the spokesperson said. The bank ultimately released the account on Jan. 19.

It seems Aboubacar mailed his Exemption Claim Form in the appropriate amount of time. Capital One initially notified him Sept. 9 of the account withholding, the bank said. Signed and dated forms addressed to the bank and creditor's attorney were mailed on Sept. 28, within the 20-day window, according to a copy of a United States Postal Service Certificate of Mailing which was obtained and reviewed by CNBC.

It's unclear what happened after that — if the bank didn't receive the forms at all, or if the bank received them and deemed them insufficient, for example. A bank spokesperson didn't respond to a request for comment on this point.

"It's a strong law, and it does work in a lot of situations," Shin said of New York's rules. "The problem is when the banks make a mistake and don't act to remedy their mistake. They leave the customer at the mercy of the debt collectors, who hold all the power."

Some banks comply with the technical aspects of the law, but in ways that prove onerous for consumers — by sending a paper check in the mail, for example, which the consumer doesn't always receive, Shin said.

Keita, who was displaced by the fire, ultimately got access to $3,600 in mid-February. She moved into a new apartment in the Bronx on March 14. Chase told Keita on March 11 that the rest of her $5,000 account would be accessible within days, according to McCune, her attorney.

Meanwhile, Woodyear sued Chase in an arbitration proceeding, seeking damages related to the freeze. The case is ongoing.

"My money is still in the bank, only because I don't know which bank is good," Woodyear said. "Once one bank burns you, you don't really know which way to go."

"Sometimes, I'm afraid to check my bank account," she added. "I'm afraid to see if it'll be frozen."