A bill to return a scenic and valuable parcel of Manhattan Beach land to the descendants of a Black couple who once operated a beach resort there advanced to the Senate floor.

Sen. Anthony Portantino, D-La Canada, chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee, determined that SB 796 had no significant state costs and applied Senate Rule 28.8, sending it directly to the Senate floor for a second reading without a hearing in the committee.

The bill by Sen. Steven Bradford, D-Gardena, passed the Senate Committee on Natural Resources and Water last month with unanimous support.

The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted unanimously April 20 to direct the county's CEO to come up with a plan to return the property to the family and to support the bill, whose passage is required to make the transfer possible.

Get top local stories in Southern California delivered to you every morning. >Sign up for NBC LA's News Headlines newsletter.

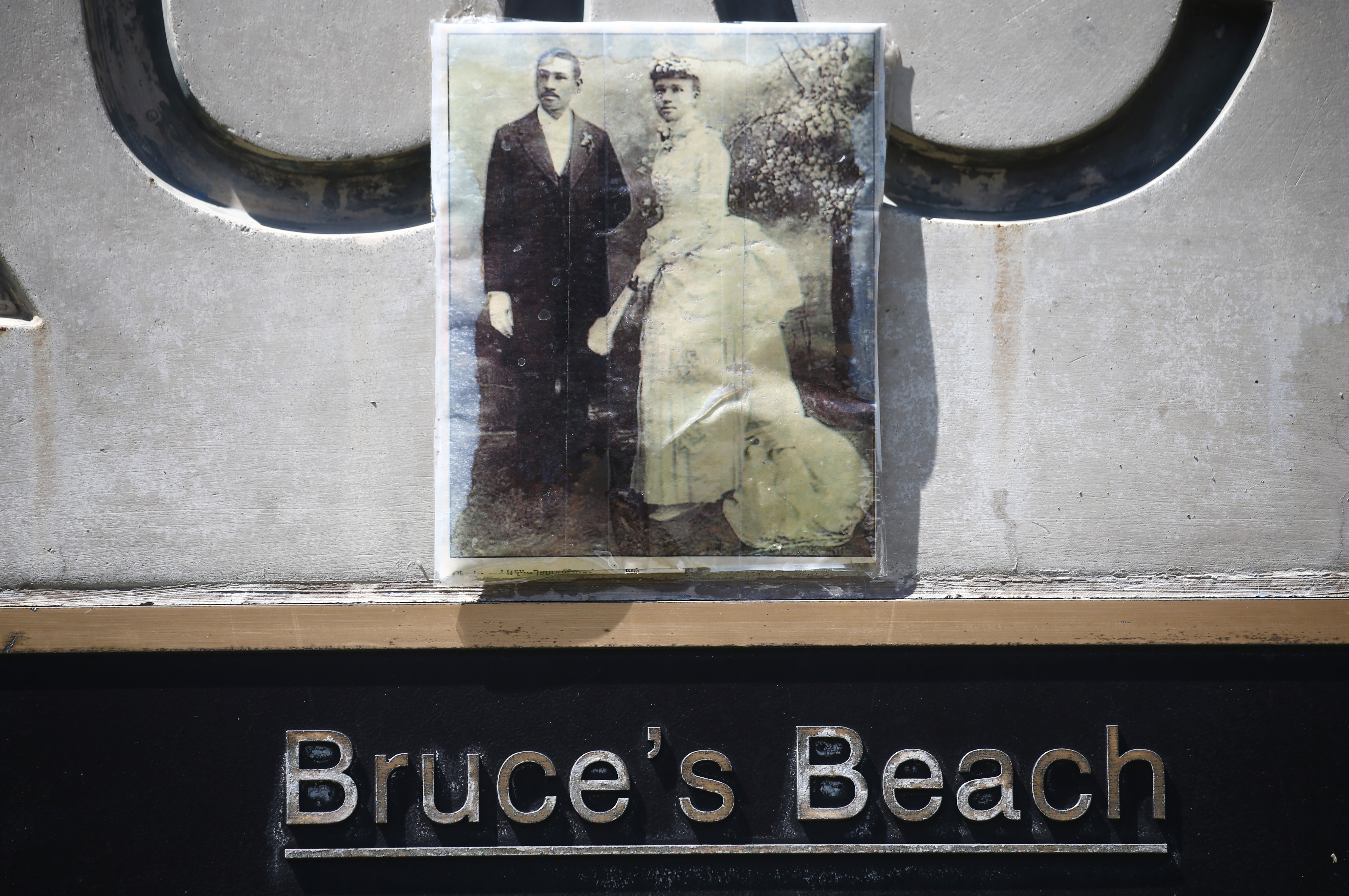

"This was an injustice inflicted upon not just Willa and Charles Bruce -- but generations of their descendants who almost certainly would have been millionaires if they had been able to keep this property and their successful business," Supervisor Janice Hahn, who introduced the motion, said in a statement following the motion's passage.

"When I realized that the county now had ownership of the Bruce's original property, I felt there was nothing else to do but give the property back to the direct descendants of Willa and Charles Bruce."

Transferring a portion of what is known as Bruce's Beach requires state legislation to remove restrictions on the land, which now houses the county's lifeguard training center.

The public seizure of the Bruce's Beach property has long stained the history of the seaside community, particularly in the past year amid a nationwide reckoning on racial injustice.

Willa and Charles Bruce purchased land in 1912 for $1,225. They eventually added some other parcels and created a beach resort catering to Black residents, who had few options at the time for enjoying time along the California coast.

Complete with a bathhouse, dance hall and cafe, the resort attracted other Black families who purchased adjacent land and created what they hoped would be an ocean-view retreat.

But the resort quickly became a target of the area's white populace, leading to acts of vandalism, attacks on vehicles of Black visitors, and even a 1920 attack by the Ku Klux Klan.

The Bruces were undeterred and continued operating their small enclave, but under increasing pressure, the city moved to condemn their property and other surrounding parcels in 1924, seizing it through eminent domain under the pretense of planning to build a city park.

The resort was forced out of business, and the Bruces and other Black families ultimately lost their land in 1929.

The families sued, claiming they were the victims of a racially motivated removal campaign. The Bruces were eventually awarded some damages, as were other displaced families. But the Bruces were unable to reopen their resort anywhere else in town.

Despite the city claiming the land was needed for a city park, the property sat vacant for decades. It was not until 1960 that a park was built on a portion of the seized land, with city officials fearing the evicted families could take new legal action if the property wasn't used for the purpose for which it was seized.

The exact parcel of land the Bruces owned was transferred to the state, and then to the county in 1995.

The city park that now sits on a portion of the land seized by the city has borne a variety of names over the years. But it was not until 2006 that the city agreed to rename the park "Bruce's Beach" in honor of the evicted family. That honor, however, has been derided by critics as a hollow gesture toward the family.